Vol. 7 Issue 3, Summer 2002

By Bruce Hopkins

The Blue Ridge along Loudoun’s western border offers wonderful opportunities to observe fall migrations of hawks and other raptors.

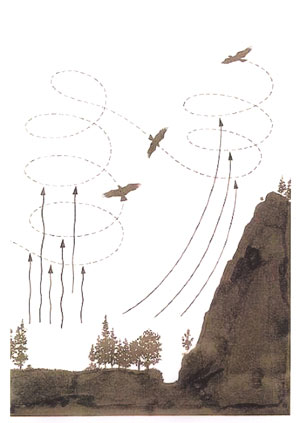

Hawks migrate along the Blue Ridge—and other Appalachian ranges to the north and south—because of thermals and deflection air currents associated with the ridges. The thermals and deflection currents help the birds conserve energy as they travel between eastern North America and their wintering areas in northern South America.

Diagram provided courtesy of the National Park Service.

Simply put, hawks primarily use the deflection currents to propel themselves forward and use the thermals for uplift.

The deflected air currents, or updrafts, are caused when northwesterly winds in the fall—and occasional southeasterly winds in the spring—are forced up and over the Blue Ridge. With outstretched wings, the birds glide on these updrafts at an average speed of 40 miles per hour and as fast as 60 mph.

In heavy winds, some hawks fly close to the ridge to avoid turbulence.

Thermals result when relatively warm air from the south side of the Blue Ridge rises and is trapped by cooler air from the north side. Moisture and dust are drawn into the rising air, which helps form cumulus clouds above the thermals.

The hawks move forward by circling upward in a thermal, gliding down to the next thermal, circling upward, and on and on. Riding thermals, obviously, is not as fast as riding deflection air currents, but it is better than waiting around in a treetop for conditions to change.

In the fall, get out your binoculars, fill up a Thermos with coffee or hot chocolate, and venture out to Snickersville Gap and other spots along the Blue Ridge to watch the migrating hawks and other birds of prey. If you are lucky, you might see a “kettle” of hawks numbering in the hundreds. ®

This article was written by Bruce Hopkins for the National Park Service and is reprinted here with their permission.