Volume 25 Issue 3, Summer 2020

by Sam Droege, native bee expert and biologist at the USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center.

Two-spotted Bumblebee on Coreopsis

Photo by Anne Owen

We know birds, we watch them, we tally them, we feed them, we keep them. They are protected by federal laws because they migrate across state and international boundaries. They were the among the first group of animals we studied and tried to conserve when we realized that, left unregulated and unprotected, birds were going extinct. No surprise that now we have many bird conservation laws, more conservation studies, and parks and refuges are set up to preserve these species. From a bird angle, this means that we target the preservation of natural habitats and basically dial the vegetation from grassland to forest depending on what species we want to benefit. There is nuance, but most of the time it is about the plant structure of an area, not about the plant species in that area.

Ah, but for bees (our 450-plus native species, that is) it is all about the plant species, not the plant structure. Furthermore the only part of the plant bees really care about are flowers — specifically the pollen of those flowers. Why is that? It’s about their babies. You see, many bee species only provide pollen to their young from a limited taxonomic group of plants. If those plants are not there, those bees are not there. They are that picky, and the very varied chemical composition (both nutritionally and in terms of distasteful — or poisonous! — compounds) of our plants reflects those choices. An example of this is Spring Beauty (Claytonia virginica), with its pink pollen, which is the plant needed by the Andrena erigeniae bee.

Brown-belted Bumblebee on Butterflyweed

Photo by Anne Owen

So, in its most compressed form, we must all realize that which blooming plants live on the forest floor, populate our wetlands, live in hedgerows, survive in lawns, live in old fields, and that we plant are critical. You cannot simply seed clover and congratulate yourself. Actions can be as simple as:

- Planting/encouraging a wide variety of native plants.

- Eliminating/discouraging invasive plants (they attract, but rarely support, native bees).

- Shifting toward maintaining open landscapes instead of planting trees on all of them.

- Greatly reducing deer herds.

- Choosing plants to use/encourage first from this list.

- Shifting from lawns to curated landscapes of native plants.

Do it, friends.

Perplexing Bumblebee on Common Milkweed

Photo by Anne Owen

“With non-native plants you can get a lot of bees coming to a number of different kinds of plants, but think of these plants as bird feeders for the crow and sparrow bees. So if you put a bird feeder in the middle of the city, you get lots of birds but you are not getting flamingos, warblers, and shearwaters, you’re getting crows, chickadees… the things that don’t need our help, but the things we love having around.”

– Sam Droege

Best Plant Genera for Native Bee Specialists in the Mid-Atlantic

Plant Genera Native Bees

Solidago, Goldenrods 35 species

Symphyotrichum, Asters 32 species

Viola, Violets 26 species

Helianthus, Sunflowers 18 species

Oenothera, Evening primrose 17 species

Salix, Willows 16 species

Eastern Carpenter Bee on Bee Balm

Photo by Amie Ware

USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab Team photo

The Andrena nida bee feeds its young only willow pollen. Willow trees have more bee specialists than almost any other plant on the continent.

USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab Team photo

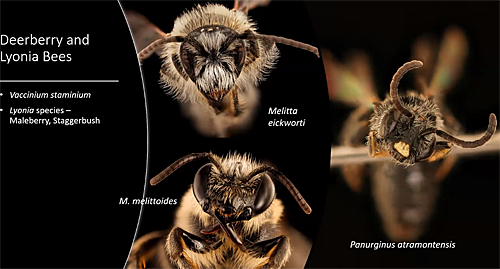

Look for Deerberry and the Lyonia species of plants, like Maleberry and Staggerbush, to see their bee specialists – Melitta eickworti, M. melittoides, and Panurginus atramontensis.

Resources:

A list of specialist bees of the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States: http://jarrodfowler.com/specialist_bees.html

Look at the photos of the USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab Flickr Page: http://www.flickr.com/photos/usgsbiml

USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab (BIML) Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/groups/usgsbiml/

Connect with Sam Droege at the U.S. Geological Survey: https://www.usgs.gov/staff-profiles/sam-droege

List of native plants for native bees from Loudoun Wildlife Conservancy, click here.