Volume 27 Issue 1, Winter 2022

Review by Steve Allen

Two young geniuses, James Watson and Francis Crick, were in a race with biochemist Linus Pauling to discover the structure of DNA. Watson and Crick won the race by sheer intellectual force, identifying the double helix structure in 1953, and leaving Pauling behind. At least this is their version of events as told in Watson’s best-selling 1968 memoir, The Double Helix.

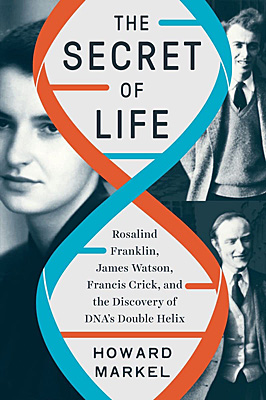

Dr. Howard Markel — physician, University of Michigan professor of medical history, and author of The Secret of Life — has a different take on the tale. In this new version, Watson is shown to be an unreliable narrator with a very big secret to conceal.

The search for the structure of DNA required three discrete steps: the first was experimental, using x-ray crystallography to photograph the molecules in a DNA crystal; the second was theoretical, interpreting the photographs to identify the placement of molecules within the crystal; the third was practical, building a physical model to represent the structure.

The search for the structure of DNA required three discrete steps: the first was experimental, using x-ray crystallography to photograph the molecules in a DNA crystal; the second was theoretical, interpreting the photographs to identify the placement of molecules within the crystal; the third was practical, building a physical model to represent the structure.

The problem with Watson’s account is that he and Crick had no part in the critical first step. They had been forbidden from working on DNA because it would have been poaching on the domain of other more senior members of their laboratory at Cambridge University. Though they toiled on other projects and talked about DNA in their spare time, they were far from discovering a solution to the crystal conundrum.

Watson’s secret was the contribution to their discovery by Rosalind Franklin. An intellectual equal and a first-rate experimental scientist, she was doing the first-step x-ray work at King’s College in London. As the only woman in a very exclusive men’s club — molecular biophysics in the early 1950s — she was met with much disrespect. Franklin was bullied mercilessly, given nicknames she hated, and mentions of her by Watson and others focused on her looks and choice of clothing rather than her scientific achievements. Not deterred by these insults, Franklin was quick to point out flaws in others’ work immediately and publicly, a quality that did not further endear her to her colleagues.

In 1951 Franklin took what some regard as the most important photograph ever taken, an x-ray photograph of the DNA crystal known as Photograph No. 51 showing the crossing of the two strands of DNA (basically a cross-section of the crystal at the X at the center of the drawing on the book cover). Although the image was meaningless to the general public, a molecular biologist could determine most of the DNA structure from that photo. Two strands (and not three, as Pauling believed) can be seen clearly, and the distance between the individual molecules on the strand is also evident. Franklin understood the implications of the photo, but instead of moving to steps two and three, she continued to take more photographs.

Several months later, Maurice Wilkins, one of Franklin’s bitter rivals, showed Photo No. 51 to Watson, who took it back to Crick, and they quickly worked out step two and built the model we now know as the double helix. In their scientific papers, interviews, and books, however, they glossed over the fact they had basically stolen Franklin’s experimental work, a serious academic crime, barely mentioning her except in an occasional footnote.

Franklin never received scientific recognition for her role in the DNA riddle. She died of metastatic ovarian cancer in 1957, possibly caused by overexposure to the radioactive isotopes used in her x-ray experiments. To add insult to injury, when Watson, Crick, and Wilkins shared the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1962, they disregarded the contribution of Franklin (who, ironically, became ineligible for the prize upon her death).

The Secret of Life is a meticulously researched history of the time and the people involved, made possible by the discovery of the scientists’ archived lab notes and personal papers. Professor Markel has finally given Rosalind Franklin the recognition she deserves, even if it comes sixty years too late.