Vol. 10 Issue 3, Fall 2005

By Nicole Hamilton

Photo by Nicole Hamilton

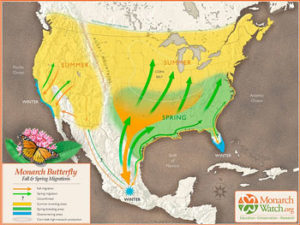

Monarchs are one of the most well-known butterflies in North America. Their migration is now quite well understood. Monarchs begin to move south in the late summer. These migrants make it all the way to Mexico where they spend the winter. That is a distance of over 2,000 miles!

In the early spring they will begin to head north. They migrate so that they can have greater access to the milkweed plant, which is necessary as food for their young. As they move north, there is also less competition for flower nectar.

Birds that migrate in the fall are seeking an abundant food supply and warmer conditions. However, the Monarch is seeking the opposite. Since they do not really feed over winter, abundant food is not important. And while they need to avoid freezing, they prefer a cool, moist area for the winter. They find this in the mountain regions of Mexico. Here, they can rest from their long journey.

While they seem fragile, Monarchs are actually strong fliers, able to fly at up to 20 miles per hour and at altitudes of over 10,000 feet. As a result of monarch tagging programs, it’s been determined that Monarchs can fly as many as 80 miles in a single day. Cape May is a terrific place in our area to view the monarch migration. In 1999, over 85,000 monarchs were counted between September 22 and November 21, and over half of these were sighted in a single day in October.

Once they arrive in Mexico, the monarchs mature and mate and by early winter, they begin their journey north, laying eggs along the way and typically finishing their journey by the time they reach Texas but nonetheless, imprinting in their babies with the information to travel north, back to our gardens as well as points even further north. The success of this migration is depended on the nectar and larval food sources that can be found along the way.

Once they arrive in Mexico, the monarchs mature and mate and by early winter, they begin their journey north, laying eggs along the way and typically finishing their journey by the time they reach Texas but nonetheless, imprinting in their babies with the information to travel north, back to our gardens as well as points even further north. The success of this migration is depended on the nectar and larval food sources that can be found along the way.

Unfortunately, pesticides, genetic engineering and destruction of “weedy” habitats where wildflowers and milkweed plants thrive have had a negative impact. At the current rate of loss of both the habitat here in the U.S. and the loss of wintering forests in Mexico due to illegal logging, it has been suggested that Monarch butterflies could be extinct within the next 30 years – a sad story that will play out in our lifetimes, for better or for worse, depending on our action or inaction.

In addition to the Monarchs, there are other species of butterflies in our area that migrate. These species include: the Painted Lady, American Lady, Red Admiral, Common Buckeye, Long-tailed Skipper, Clouded Skipper, Cloudless Sulphur, Mourning Cloak, Question Mark, Fiery Skipper and Sachem.

Often, these migrations go unnoticed but in the fall, Cloudless Sulphurs, Mourning Cloaks, and Question Marks can be found flying southward on the soft tailwind of a passing cold-front in groups of thousands like the Monarchs do. Exactly where all of these butterflies go is not known although many will overwinter in Southeastern and Gulf states and Painted Ladies will go as far as northern Mexico.

In addition to the two-way migrations, there are also some butterflies that perform a one-way emigration whereby in the late summer or early fall, when there has been a particularly good breeding season, the butterflies will have an irruption and emigrate northward rather than stay in their usual southern areas.

Most of these butterflies that fly northward in the fall will die because they cannot withstand the colder temperatures of winter but especially in this time of global warming, this is the means they use to gradually expand their range.

Clouded Skipper.

Photo by Laura McGranahan

For butterfly watchers, irruptions are part of the excitement of fall and in Cape May, for example, people keep their eyes peeled in hopes of seeing species as the Cloudless Sulphur, Little Yellow, Sleepy Orange, Clouded Skipper, Fiery Skipper, Sachem, and even such rarities as the Gulf Fritillary, Long-Tailed Skipper, Eufala Skipper, and Ocola Skipper which typically live further south or even as far as Mexico.

Things We Can Do:

Gardening for Butterflies: From The Butterfly Gardener’s Guide, by Pat and Clay Sutton: “Understanding the complexities of butterfly migration is a major aspect of butterfly watching, and attracting migrants is one of the greatest pleasures of butterfly gardening. They may be here today and gone tomorrow, but a healthy and diverse butterfly garden can be an important pit stop where migrating butterflies can refuel for their continuing journey.

This is particularly true for Monarchs and other “two-way” migrants such as Red Admiral and Painted Lady, but important even for emigrants. Nectar-rich fall-blooming flowers, such as goldenrod, Solidago, provide migrating Monarchs with much-needed nutrients to sustain them during their long journey to Mexico.

While it is vitally important to support conservation efforts in Mexico, gardeners along the migration route can help Monarchs by growing milkweeds. The plants are sought for egg laying by northbound females in spring and by ensuing generations of Monarchs through the summer, while milkweed nectar attracts many species of butterflies, including Monarchs.

As the last generation of Monarchs for the year makes its arduous journey south in the fall, individuals can cover long distances in a day. They need an energy boost from nectar-rich flowers that bloom late in the season, such as joe-pye weed (Eupatorium), asters, goldenrods (Solidago), and sedums. At night, they look for safe roosting spots in the branches of trees and shrubs. Join with your neighbors to create safe-travel wildlife corridors of pesticide-free milkweeds, nectar plants, hedgerows, and trees.”